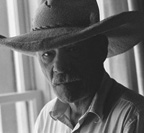

Steve Darland

Steve Darland • Written April 2011

Darland worked, starting at age 18, in the weekly newspaper business in Kent during studies at UW, then in the agency business (and politics) in Seattle, Washington, D.C., New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles (the last 3 cities with JWT), then worldwide for J. Walter Thompson as Director of Brand for all agency clients - and as a member of the agency’s 10-person Executive Committee that manages JWT’s 200+ worldwide offices.

In Seattle and while still in college, Steve worked at Frederick E. Baker Advertising, Inc., then after returning west, he worked at McCann and with Don Kraft. Between these last 2 Seattle agency jobs, he founded The Consortium in which his marketing services firm, Concept Management, Inc., was a leading player in work on public service, non-profit, often government or community assignments and those in the arts. He was a two-term Washington State Arts Commissioner.

Steve and his wife Jane now own and operate several small, adjacent organic farms in the historic adobe village of Monticello, New Mexico at a mile altitude, growing for the local farmers’ market – with several specialty products, including their rare, acclaimed traditional-style balsamic vinegar, aged since 1998. (www.organicbalsamic.com). Edible (Santa Fe) magazine named them 2011 “Artisans of the Year” for New Mexico.

Having a clear, stated vision of what you are trying to accomplish is the single best piece of advice I can give anyone. And I give it here in the first paragraph so I don’t forget it.

It is always fresh in my mind that Nietzche, the highly quotable philosopher, said, “The greatest human failing is we forget what we set out to do.” This is true n all life, both personal and business. I have benefitted from remembering and applying this admonition.

I use personal notes below to demonstrate this. But steady intention is at the center of what I do professionally in client marketing: get the most senior person in a client organization to endorse what they set out to do, study the hardcore facts of the case, break the task into natural pieces, and do them, creatively, and in concert. Steadily, miracles seem to happen in creative work, in the marketplace—even in your larger life.

It is my 39th year of marriage and 53rd year since someone first paid me to work in something like marketing and advertising. In the business case, first in 1963 newspaper advertising in a “free weekly shopper” newly started in Kent by Jerry Robinson’s Associated Weeklies.

I was single, and the six-day-a-week full-time job paid for tuition at the UW and my living costs. School was full-time too, but two full-time schedules at once seemed easy, since my work and my studies merged into the single theme and direction of my life.

My purpose was to pay for a degree in Journalism advertising at the UW’s School of Communications and to learn everything possible about the ad agency business from the then national experts (and key text book authors), Willis Winter and Dan Warner.

My larger and longer-range purpose was to have a highly successful career at J. Walter Thompson. When their recruiter came to campus late in my senior year, I was hired during the interview and started that fall, taking a 50% pay cut from my last job in Seattle before heading to New York. (In my senior year of college, I was a junior account executive at the wonderful ad agency, Frederick E. Baker, Inc. Founder Fred was two generations ahead of me and from time-to-time wore spats—spats!—to work as part of his resplendent vested business clothing.

Having lost my pay-cut half of what I earned with this job change, I found myself living in a much more expensive place than Seattle. Plus (or should I say minus), taxes for the City, New York State and U.S. took nearly another half of the remainder, so I needed to find roommates, something I strictly avoided (and enjoyed) during college. I first roomed with several UW buddies (including the now-famous copywriter and creative leader Bill Lane). So, by sharing a small one-room brownstone apartment on the-then wildly unfashionable upper West Side with three, sometime four people, I could almost afford to sleep.

Eating was more of a challenge. But it turned out that there were good ways to handle this even without a budget. JWT had 11 floors above Grand Central Station, each an acre, with one of the half-floors dedicated to an excellent three-meals-a-day cafeteria, serving 1,500 employees. There, if you arrived before 7am, you got any breakfast free—and if you worked past 7pm, you got any dinner free. (The executive bar opened between 5 and 7pm and all drinks were 10 cents, very cheap even then!) As an account rep on several heavily advertised Seagrams brands, all the food and upscale-magazine reps wanted to know where I wanted to eat lunch, every day, any day. Collectively, we worked our way through NYC’s famous and fabulous restaurants.

My purpose was to live at least better than I had in college, but now I was doing it in 1967 NYC on about $3,000/year, after taxes.

Over time, the food arrangement worked better than the apartment; sometimes guests or unplanned parties crowded out even paying tenants. But I caught an unbelievable break at work, though it started badly. I was told I had earned the right to have an office, instead of a cubicle, but that there no offices available right then. Because I had increasing numbers of clients visiting the agency, I pushed back pretty hard—and was very reluctantly walked upstairs to, well, paradise. (Their emphatic rule for me: “Don’t show anyone else working here your office.”)

The well-appointed 1926 JWT boardroom in the Thompson manner was still part of the offices and had an always-absent occupant who ran the Rolex account in Europe and was seldom in NYC. So, I would share with a phantom officemate “our” 15’ x 30’ “office” with a boardroom table, large desk, working fireplace, two full walls of windows (since it was a corner office), large closet, bathroom/shower and lockable office door, probably unique for JWT. It also has a couch big enough for sleeping. I now had my “better” apartment at work.

If my ultimate purpose was to eat, sleep and breath the behemoth J. Walter Thompson, I was living that dream—on $3,000 a year. Remember, goals are able to surpass the resources you have to meet them, if you truly focus. (What if my goal had been an amount of salary rather than success at JWT? Then, a numeric objective would have been in contest with my higher, overall mission.)

Life was never perfect, but it always looked a lot like I imagined it. Why is that? It could be magic or a long series of happy accidents. Also, there’s this thing called intention; you see something clearly and regularly, and it materializes. Or could it just be discipline? You make a plan and work the plan—and if it’s even modestly realistic, you make it happen. Wanting a more scientific explanation? Quantum physics, among other things, says that intention is a real force in our reality.

I should note too that Seattle’s Lou Tice of The Pacific Institute has created a large, very successful organization that works around the world with governments, businesses, organizations and individuals in materializing their plans. TPI’s well-tried system of affirmations may work because it gets all players to continuously focus on what they set out to do. (I was out of the country when Lou recently had his 75th birthday—and I was sorry to miss the event. He was my high school football coach and has been a friend for two-thirds of his life and more of mine. Lou often reminds me that my father named his company.)

Whatever the mechanics of realizing your mission or goals of dreams, remember what you set out to do—and Lou would say to affirm it daily, clearly.

After seven years of working on the East coast, I longed for the West. My wonderful new young wife Jane and I moved back to Seattle and started a family; they remain the emotional center of our life. Work with local agencies was something of a letdown (other than the many people I got to know—Tim Girvin being among the first and with whom I still have regular contact, plus Bill Hoke, who continues bravely to have his original “fire” going steel hot).

So we started Concept Management, Inc. to sell marketing advice—plus we wanted sufficient family time to forge a group of healthy individuals who knew and liked each other. Since we soon learned our firm was too small to get big contracts, we founded The Consortium, which had our little outfit join dozens of others to create Seattle “biggest agency.” Though virtual, we had many talented professionals from every marketing skill group; each had decided they could no longer work in an agency format. So, we set out to apply our collective skills for public, non-profit accounts.

Our most important early client was the just-new public utility, Metro Transit. MARKETING publisher Larry Coffman was our senior client. Our advertising was super (“Take me, I’m yours” and “I’m no dummy, I take the bus”), results exceed plan and, as a happy by-product, we transformed bus-sign advertising into a hot new King County medium. Another 20+ clients—like the Washington State Ferry system (“Spend a day overseas.”)—hired us; we worked our way to an impressive and successful client list. Seven years doing this gave great joy—and little profit.

Back I went to a regular paycheck at an agency, until Bill Lane re-entered my life, asking me to move to San Francisco and help him rebuild JWT/San Francisco and Los Angeles. Though Bill soon was plucked out of the equation to slay dragons back in NYC, the Bay Area office billing was lifted almost 400% to nearly $300 million with clients paying 15% commissions or more. We were profitable and had the independence that comes with blowing away earning targets. We also were producing some of the best creative for JWT worldwide, had a strong, happy and rewarded 170-person staff in beautiful San Francisco waterfront offices, and were providing unique agency-wide leadership early in the developing digital age.

But the point? My long-term intention with J. Walter Thompson was now being reborn and realized, even with a gap in time. Goals don’t easily go away, if they are sincere; and if they are difficult, they may just take longer. I was made a regional president, corporate EVP, was named to the U.S board of directors, then the worldwide board, then to the 10-person executive group, which runs JWT’s 200+ of worldwide offices. My last four years included assignment as JWT’s worldwide brand communications director. It all was a dream come true and it was rewarding in every way.

So, what else could we set out to do? Become organic farmers, of course. No, it’s not a natural progression, but neither is the prospect of “early retirement” once you start to experience it. Nor is the world we now live in one of simplicity, sense and predictability. Our kids were either finished with or away at college. I was traveling a million miles a year to far-flung JWT outposts, to clients and management meetings. Still in my early fifties, I decided to stop near the top.

So, about 18 years ago, we bought land and a few tumbled down adobe houses in mile-high New Mexico and started our fix-up while there was still cash flow. By the time we moved full-time to our village of Monticello (pop. 40), grapes, trees and gardens were growing. We did the “local” thing with total involvement in our little town, and also in the nearby bigger town, Truth or Consequences, NM, where we helped start the first farmers’ market, a place where we still purvey organic fruits, vegetables, nuts, herbs, flowers and a slew of products we make in our own little Monticello commercial kitchen.

Our biggest leap was to begin the truly endless process of making traditional balsamic vinegar—what the Italians call Aceto Balsamico Traditionale. The best known, most commonly used balsamic in the U.S. is called industriale in Italian, since it can be made in a day, is not aged, and is more chemistry than tradition. It’s the difference between cheap cologne and historically famous perfume. We wanted to make the good stuff, which traditionally has its first milestone at 12 years and the next at 25 years old. (We have tasted some made starting in the 1660s, Amazon also is offering some that’s hundreds of years old, and the good stuff at DeLurenti’s in the Pike Place Market is 25, 50 or 100 years old, with cost usually starting at $150 for a 100ML bottle. That’s the price for our 130ML bottle.)

Our balsamic is now in its 14th year of aging, but before that, start-up (building a building, initializing grapes, ordering Italian casks, learning irrigation, etc.) took a prior four years. Right now, today, as usual this time of year, I am pruning the grape plants, solo, which takes about two weeks per year. So, when our balsamic is 25 years old, I will have spent the total of a full year, just pruning. You begin to get the idea that this is a handcrafted, not mass, product—from pruning grapes to packaging the aged balsamic—and it’s one of life’s rare marketing challenges: low awareness, high price, small product in very limited production (700 bottles/year).

My good friend for the last 50+ years, Ken Robinson, son of Jerry (yes, being known by the Robinson family helped get my newspaper job way back when) recently visited Monticello and did fabulous photography of our place and us. A few of those shots accompany this article, as requested by my old client, Larry Coffman. Right now, too, I am reading (on deadline) the manuscript of Bill Lane’s book “The Fire in the Belly: Life in the glory days of advertising”, about our mutual time at J. Walter Thompson. Tim Girvin is “threatening” to visit soon. Just helped the fact-check lady at Bon Appetit magazine put to bed a piece including our balsamic for their May issue—and recently agreed to do a tasting at the fabulous Seattle-area Cafe Juanita on June 3. And while NM’s Spring winds whip the vineyards—and me—in these bright 80F days, I have my hands full with pruning, the grunt work of luxury.

So it seems as if big pieces of my past have returned (or like the weather, been improved), while my dreams continue to materialize here and now, in the middle of nowhere, as I do the farm labor for a timeless and rare food product no one else makes commercially outside of Italy (Even my four enjoyable years of Italian language study at the UW now payoff in navigating the native language of balsamic.)

But I have moved from the abstract to the tangible, still thinking, but fully hands on. This isn’t advertising anymore. See our Website at www.organicbalsamic.com.

Bumper strip strategy summary: Remember what you set out to do. Keep focused. Work hard. Do the same for family and clients. Be your own client. Take time to learn. Reach for your highest dream. Be anxious to change. Be happy. Farm vehicle bumper strip: Plant, water, weed, prune, harvest.